‘Myth busting’ guide is withdrawn

27 March 2019

We are delighted that the Department for Education has withdrawn the ‘myth busting’ guide after a judicial review application by Article 39 children’s rights charity. Here are some news reports:

Guardian newspaper (24 March 2019)

Children and Young People Now (25 March 2019)

Community Care (25 March 2019)

Family Law (25 March 2019)

Big Issue (26 March 2019)

What’s wrong with the Department for Education’s ‘myth busting’ document?

12 November 2018

While waiting for responses to several freedom of information requests to the Department for Education and Ofsted, Article 39 children’s rights charity has produced a table setting out the inaccuracies in the Department for Education’s ‘myth busting’ document, which remains published on its Children’s Social Care Innovation microsite.

What’s wrong with the ‘myth busting’ document Nov 2018 (prepared by Article 39)

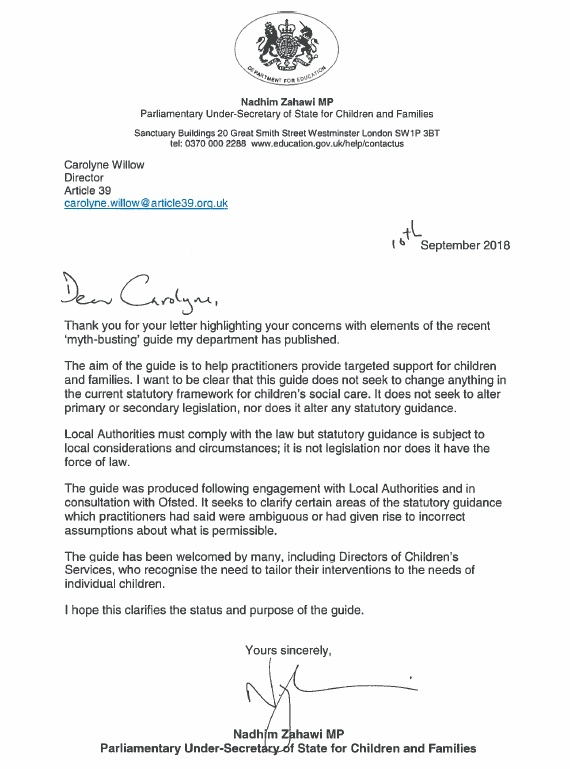

Minister responds to joint letter of concern

50 organisations and social work experts urge withdrawal of key parts of new ‘myth busting’ guide about England’s care system

Open letter to Nadhim Zahawi MP

Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Children and Families

Department for Education

4 September 2018

Dear Minister

‘MYTH BUSTING’ GUIDE ON STATUTORY GUIDANCE

We write to express our deep concern about the ‘myth busting’ guide, which was recently published on your Children’s Social Care Innovation Programme microsite.

Several parts of the document incorrectly describe the statutory framework for England’s care system. Following legal advice, we ask that these sections be immediately withdrawn to avoid the risk of confusion and to prevent any harmful effects on vulnerable children and young people, and those caring for them.

It is of utmost importance that legal certainty be maintained when it comes to the care and protection of vulnerable children and young people looked after by local authorities. To frame as ‘myths’ a series of questions about the care system’s statutory framework is unhelpful. This is because it gives the impression that key parts of current social work knowledge and understanding are untruths.

This ‘myth busting’ guide is available online, it carries your Department’s logo and contains the statement that “all of the responses below have been agreed by the Department for Education and their lawyers in consultation with Ofsted”. It is a reasonable assumption that those reading the guide will view it as having official approval and being intended to widely impact social work practice.

Although the so-called myths are not always clearly expressed, there are statements in the document which undoubtedly run counter to the current statutory framework. Whether intended or not, this could be construed as an encouragement to local authorities to act in contravention of the statutory framework.

Should amendments to regulations and statutory guidance be seen to be necessary, we ask that proposed changes be subject to proper consultation. If the reason for clarification and/or changes to the statutory framework is because of widespread misunderstanding, we would ask that the Department clearly set out: the myths which are believed to currently exist; who is said to believe these myths; and why they are, indeed, myths.

Below we set out our principal concerns. We have sought to confine our comments to interpretations of the current statutory framework, rather than providing justification for the law as it stands.

| Can we have one social worker for children and foster carers when a child is in a stable, long term placement? |

The guide states “The current framework does not prevent such flexibility”. We contend that this is not a correct interpretation of the statutory framework.

Children Act 1989 statutory guidance on fostering services distinguishes between foster carers’ supervising social worker and the child’s social worker, and explains:

Every foster carer should be allocated an appropriately qualified social worker from the fostering service (the supervising social worker) who is responsible for overseeing the support they receive. It is the supervising social worker’s role to supervise the foster carer’s work, to ensure that they are meeting the child’s needs, and to offer support and a framework to assess the foster carer’s performance and develop their skills. They must make regular visits to the foster carer, including at least one unannounced visit a year.[1]

Separate care planning statutory guidance describes the safeguarding role of visits to the child by the child’s social worker:

As part of their arrangements for supervising the child’s welfare the responsible authority has a duty to appoint a representative to visit the child wherever he or she is living [regulations 28 to 31]. Visits form part of a broader framework for supervising the child’s placement and ensuring that his/her welfare continues to be safeguarded and promoted. Visits therefore have a number of purposes, including to:

- support the development of a good relationship between the child and the social worker which will enable the child to share his/her experiences, both positive and negative, within the placement;

- provide an opportunity to talk to the child and to offer reassurance if s/he feels isolated and vulnerable while away from family and friends;

- evaluate and monitor the achievement of actions and outcomes identified in the care and placement plan and to contribute to the review of the plan;

- identify any difficulties which the child or carer may be experiencing, to provide advice on appropriately responding to the child’s behaviour and identify where additional supports and services are needed; and

- monitor contact arrangements, to identify how the child is responding to them and to identify any additional supports carers may need to support positive contact arrangements.[2]

As acknowledged in the guide, the Fostering Services National Minimum Standards[3] also distinguish between the child’s social worker and the supervising social worker.

Separate regulations deal with the approval, supervision and support given to foster carers, and the actions required by local authorities to safeguard and promote the welfare of individual children living in foster care.

Care planning regulations set out the frequency of social worker visits to children[4] and require that the child is seen in private, unless s/he has sufficient understanding and refuses this.[5] Dispensing with the child’s social worker could significantly undermine the statutory purpose of this ‘seeing the child alone’ duty. There is a very real danger that children will perceive the single social worker as working for ‘the adults’ and attached to the particular placement, rather than being there for them. The social worker themselves may additionally feel professionally conflicted, especially when there are concerns about a placement.

The Department’s own data shows that children were moved from a foster care placement 360 times in England in 2016/17 because of standard of care concerns, and 430 times because of a child protection allegation.[6] We do not believe that these figures are mirrored by the number of times action has been taken to deregister foster carers, indicating that the current system of separate support seeks to ensure that children are properly protected, while making certain foster carers are fairly assessed and managed.

Where, following a visit to the child, the local authority has concerns about the child’s welfare, a review of the child’s case must be arranged.[7] This will ensure scrutiny by the child’s independent reviewing officer. Allowing fostering providers to effectively supervise themselves inevitably undermines the present statutory framework.

Although regulations (as amended in 2015) state that ‘long term’ means the child is intended to stay with their present foster carers until they cease to be looked after[8], the guide gives no indication as to how long a child should have been in a placement before their own social worker can be removed. Similarly, no definition of ‘stable’ is provided. It is also not clear whether a single (supervising) social worker could be expected to take on the statutory responsibilities of more than one child in a placement. None of this appears in existing statutory guidance and regulations because it is not current law or policy.

There are very strong child-centred reasons for the current statutory framework. It cannot be assumed that the interests of foster carers and child/ren will be the same, or will be possible for a single social worker to navigate. For example, it is not unknown for foster carers to take on a second child inappropriately and contrary to the wishes and needs of a child already settled with them because they are ‘approved’ for two children and their finances are based on this. Then there is the important role the child’s social worker has in eliciting and responding to the child’s wishes and feelings about seeing parents, siblings and other family members (or former carers). These are not fixed, and often change as a child gets older. In the current, established model, the child’s social worker may be the social worker for separated children in sibling groups or for the family where siblings are still living. The work involved in helping children preserve relationships which are extremely important to them cannot be underestimated.

It is pertinent that the 2013 DfE consultation which led, in 2015, to a more flexible model of social work support for children in long term foster care did not propose a merger of the roles of the supervising social worker and the child’s social worker. Indeed, this explained:

It is important that each member of the team – the foster carer or residential worker, supervising social worker and child’s social worker – understands and is able to perform their own role and that they also understand and respect the roles of the other members of the team.[9]

Revisions to care planning regulations introduced in 2015, as a consequence of the 2013 consultation, similarly did not lead to a merger of the two social workers. The Explanatory Memorandum explicitly refers to the child’s social worker:

4.14 As part of the local authority’s duty to safeguard and promote the child’s welfare, an officer of the authority must visit the child in their placement at a specified minimum frequency. For the most part these visits will be carried out by the child’s social worker…[10]

| Can a Personal Adviser take on the role of the supervising social worker for foster carers, where the young person is staying put? |

The guide states that, although they have “some reservations”, the DfE and Ofsted “would welcome details of any proposed new ways of working” that would allow Personal Advisers to take on the role of a supervising social worker. The guide states this would be where a young person is in a Staying Put arrangement, but no other children are fostered within the family.

The absence of (other) foster children in a Staying Put arrangement does not diminish the local authority’s statutory duties in respect of monitoring and supporting the Staying Put arrangement.[11] It also does not change the statutory function of Personal Advisers, which are set out in leaving care regulations:

a) to provide advice (including practical advice) and support;

(b) where applicable, to participate in his assessment and the preparation of his pathway plan;

(c) to participate in reviews of the pathway plan;

(d) to liaise with the responsible authority in the implementation of the pathway plan;

(e) to co-ordinate the provision of services, and to take reasonable steps to ensure that he makes use of such services;

(f) to keep informed about his progress and wellbeing; and

(g) to keep a written record of contacts with him.[12] [Emphasis added]

Statutory guidance explains: “Monitoring the ‘staying put’ arrangement will form an important part of the support package. The pathway planning process should review the arrangement on an on-going basis and progress should be recorded as part of that process”.[13]

Case law is clear that Personal Advisers cannot take on the role of social workers or the local authority in preparing or reviewing Pathway Plans.[14] It is difficult, therefore, to see how the Personal Adviser could take on the role of a supervising social worker within the current statutory framework. Munby J (as he was then) in Caerphilly explained:

Part of the personal adviser’s role is, in a sense, to be the advocate or representative of the child in the course of the child’s dealings with the local authority. As the Children Leaving Care Act Guidance puts it, the personal adviser plays a ‘negotiating role on behalf of the child’. He is, in a sense, a ‘go-between’ between the child and the local authority. His vital role and function are apt to be compromised if he is, at one and the same time, both the author of the local authority’s pathway plan and the person charged with important duties owed to the child in respect of its preparation and implementation.[15] [Emphasis added]

| Can supervising social workers visit less frequently in stable and long term placements? |

This section of the guide concludes with, “A judgement should be made on a case by case basis as to the suitability of the frequency of visit and if the foster carer has the capacity to meet the child’s needs with the minimum frequency of a visit once a year”. As it earlier states, one visit a year is the minimum number of unannounced visits.

Statutory guidance in respect of fostering services requires that supervising social workers “must make regular visits to the foster carer, including at least one unannounced visit a year” and “The fostering service should also provide support to the sons and daughters of foster carers and other people living in the foster carer’s household who play an important part in supporting children in placement”.[16] Fostering services providers, whether local authorities or independent, “must provide foster parents with such training, advice, information and support, including support outside office hours, as appears necessary in the interests of children placed with them”.[17] To suggest that one visit a year to a foster family would meet the current statutory framework is an incorrect interpretation of the current statutory framework. As with the above question on the removal of separate social workers for children and foster carers, the guide notably omits to specify what is meant by “stable and long term”. This imprecision could put children at risk.

| Can social workers visit less frequently than the normal six weekly basis in stable and long term placements? |

Care planning regulations (as revised in 2015) state that children in long-term foster placements – where the child will live until they cease to be looked after[18] – can be visited as little as twice a year when they have been in that placement for at least one year but only if the child has sufficient understanding and agrees.[19] This is a very important caveat that is not mentioned in the guide. It effectively means that the fewer number of visits cannot be applied to babies, young children and others who do not have the capacity to understand the implications of reducing local authority oversight.

| Do we always have to conduct an independent return home interview? |

This part of the guide contains three interpretations of the statutory framework which are incorrect.

First, it states that children should always be offered a return interview. This differs from the children who run away or go missing statutory guidance, quoted in the guide, which states children must be offered a return interview.[20]

Second, the guide states if the child does not want to be interviewed, then the interview does not have to take place. The statutory guidance does not say this (though there is reference to children refusing) and we believe this statement risks undermining the clear expectation that professionals will do their utmost to encourage children to speak with an independent person about why they went missing. The guide’s advice that “The offer must be genuine and the young person encouraged to accept” is weakened by the “but” that follows. “Refusal” is not the same as “does not want”. The former reflects an informed choice. The latter is an emotional response, which may or may not be based on an understanding of what is involved or the importance of the process. A child may not want to be interviewed but, when given an explanation as to why return home interviews are undertaken, and what they entail, may agree to do something that s/he would rather not do because the benefits outweigh the concerns s/he has.

Third, the guide states the child can choose who they want to conduct the interview, if they do not want an independent interviewer. The statutory guidance does not say this in respect of children generally. It says the return home interview “is normally best carried out by an independent person (ie, someone not involved in caring for the child) who is trained to carry out these interviews and is able to follow-up any actions that emerge”.

For looked after children, the expectation in the statutory guidance is that the return home interview “should usually” be conducted by someone “independent of the child’s placement and of the responsible local authority”. However, an “exception” to this is permitted when a looked after child “has a strong relationship with a carer or social worker and has expressed a preference to talk to them, rather than an independent person, about the reasons they went missing”. But the statutory guidance adds: “The child should be offered the option of speaking to an independent representative or advocate”.[21]

The guide omits to reference the provision in existing statutory guidance that parents or carers “should be offered the opportunity to provide any relevant information and intelligence of which they may be aware” when a child “refuses to engage with the independent interviewer”.[22]

Although the guide states “We would expect good practice to be that the reasons for [the child’s refusal] are noted and recorded”, no advice is given in the guide as to the need to be aware that children may be under duress to decline an interview, or under pressure to ‘choose’ a particular individual to conduct the interview (who could be the very person they have run away from). We fear this recording refusals advice dilutes the strong message of the statutory guidance that return home interviews are a crucial safeguard.

| Can we integrate the Youth Offending Team assessments within a looked after child remand assessment? |

The guide states “A single practitioner of either discipline could lead the combined assessment, but aspects of safeguarding and welfare must be completed by a social worker”. We believe this aspect of the guide undermines the statutory purpose of granting looked after status – and protections – to all remanded children.[23]

Statutory care planning guidance encourages partnership working but does not absolve local authorities of their duties relating to care assessments, reviews and visits. It states:

When undertaking assessments, reviews and visits, it is essential to understand the differing roles of the various partner services. The designated authority should work with other services e.g. YOTs. This may include combining meetings and regularly sharing information to support effective practice, in order to ensure the child’s needs are met and to minimise burdensome requirements on the child to participate in multiple assessments”.[24] [Emphasis added]

Given the centrality of the child’s welfare and safeguarding (which includes their future care and education outside of any criminal justice sanctions) in the statutory framework, and this being the very reason remanded children were granted looked after status, it is regrettable the guide suggests this form only “aspects of” the child’s assessment.

| Does an Independent Reviewing Officer (IRO) have to chair Child Protection conferences where their looked after children’s situation is being assessed? |

The ‘myth busting’ guide omits the crucial two preceding paragraphs of the statutory guidance, which are more favourable to the IRO chairing a child protection conference where their looked after child’s situation is being assessed:

Where a looked after child remains the subject of a child protection plan it is expected that there will be a single planning and reviewing process, led by the IRO.

The systems and processes for reviewing child protection plans and plans for looked after children should be carefully evaluated by the local authority and consideration given to how best to ensure the child protection aspects of the care plan are reviewed as part of the overall reviewing process leading to the development of a single plan. Given that a review is a process and not a single meeting, both reviewing systems should be aligned in an unbureaucratic way to enable the full range of the child’s needs to be considered in the looked after child’s care planning and reviewing processes.[25] [Emphasis added]

CONCLUSIONS

Given the degree of inconsistency with established law, we have been advised the guide exposes local authorities to more judicial review cases. However, the vulnerabilities of looked after children and young people inevitably mean that many will be unaware that their corporate parents – in following this guide – are not acting consistently with the statutory framework.

As Minister with responsibility for the care system, we urge you to rectify this situation by withdrawing the above sections of the guide and ensuring that any further guidance is published following proper consultation, and that it has a clear status.

We remain fully committed to working in partnership with you and the Department in the interests of children, young people and families, and look forward to hearing from you soon.

All good wishes

The Aire Centre

Article 39

Association of Independent Visitors and Consultants to Child Care Services

Association of Lawyers for Children

Association of Professors of Social Work

Association of Youth Offending Team Managers

Become

British Association of Social Workers England

The Care Leavers’ Association

Children England

Child Rights International Network

Coram Children’s Legal Centre

Coram Voice

ECPAT UK

Family Action

The Fostering Network

Howard League for Penal Reform

Independent Children’s Homes Association

Just for Kids Law

The MAC Project (Central England Law Centre and the Astraea Project)

Nagalro, Professional Association of Children’s Guardians, Family Court Advisers and Independent Social Workers

National Association for People Abused in Childhood (NAPAC)

National Association for Youth Justice

National Association of Independent Reviewing Officers

National IRO Managers Partnership

NYAS (National Youth Advocacy Service)

Parents Of Traumatised Adopted Teens Organisation (The Potato Group)

Refugee Council

Social Workers Union

Social Workers Without Borders

Southwark Law Centre

UNISON

Dr Maggie Atkinson, Children’s Commissioner for England 2010-2015

Sir Al Aynsley-Green, first Children’s Commissioner for England 2005-10; now visiting Professor of Advocacy for Children and Childhood, Nottingham Trent University

Wendy Bannerman, Director of Right Resolution CIC

Jay Barlow, Napo National Vice-Chair

Liz Davies Emeritus Professor of Social Work, London Metropolitan University

Anna Gupta, Professor of Social Work, Royal Holloway University of London

Pam Hibbert OBE

Ray Jones, Emeritus Professor of Social Work, Kingston University and St George’s, University of London

John Kemmis, former Chief Executive Voice, NAIRO Patron and Article 39 Expert Panel member

Dr Mark Kerr, Managing Partner, The Centre for Outcomes of Care

Jenny Molloy, Author, Adviser and Trainer

David Palmer, Lecturer in Criminal Justice Services, University of Northampton

Peter Saunders, Founder NAPAC

Mike Stein, Emeritus Professor, University of York

June Thoburn CBE, Emeritus Professor of Social Work, University of East Anglia

Dr Nigel Thomas, Professor Emeritus of Childhood and Youth, University of Central Lancashire

Judith Timms OBE, Founder and Trustee of the National Youth Advocacy Service (NYAS) and a Vice President of the Family Mediators Association

Jane Tunstill, Emeritus Professor of Social Work, Royal Holloway, London University

Copied to:

Isabelle Trowler, Chief Social Worker for Children and Families

Yvette Stanley, National Director for Social Care, Ofsted

Dame Glenys Stacey, HM Chief Inspector of Probation

[1] HM Government (2011) The Children Act 1989 Guidance and regulations. Volume 4: fostering services, paragraph 5.67.

[2] Department for Education (2015) The Children Act 1989 guidance and regulations. Volume 2:

care planning, placement and case review, paragraph 3.230.

[3] Issued under the Care Standards Act 2000.

[4] The Care Planning, Placement and Case Review (England) Regulations 2010.

[5] Regulation 29 The Care Planning, Placement and Case Review (England) Regulations 2010.

[6] Department for Education (2017) Children looked after in England including adoption: 2016 to 2017. Table B3: Reason for placement change for children who moved placements in the year.

[7] Regulation 30 The Care Planning, Placement and Case Review (England) Regulations 2010.

[8] Regulation 2(1) The Care Planning, Placement and Case Review (England) Regulations 2010 as amended by The Care Planning and Fostering (Miscellaneous Amendments) (England) Regulations 2015.

[9] Department for Education (2013) Improving permanence for looked after children. Consultation, paragraph 8.2.

[10] Explanatory Memorandum to The Care Planning and Fostering (Miscellaneous Amendments) (England) Regulations 2015.

[11] Section 23CZA(3) Children Act 1989.

[12] Regulation 12 The Children (Leaving Care) (England) Regulations 2001.

[13] Department for Education (January 2015) The Children Act 1989 guidance and regulations. Volume 3: planning transition to adulthood for care leavers, paragraph 7.42.

[14] R (J) v Caerphilly County Borough Council [2005] EWHC 586; R (Deeming) v Birmingham City Council [2006] EWHC 3719; R (A) v London Borough of Lambeth [2010] EWHC 1652.

[15] R (J) v Caerphilly County Borough Council [2005] EWHC 586 [30]

[16] HM Government (2011) The Children Act 1989 Guidance and regulations. Volume 4: fostering services, paragraphs 5.67 and 5.68.

[17] Regulation 17(1) The Fostering Services (England) Regulations 2011.

[18] Regulation 2(1) The Care Planning, Placement and Case Review (England) Regulations 2010 as amended by The Care Planning and Fostering (Miscellaneous Amendments) (England) Regulations 2015.

[19] Regulation 28(3A) The Care Planning, Placement and Case Review (England) Regulations 2010 as amended by The Care Planning and Fostering (Miscellaneous Amendments) (England) Regulations 2015:

(3A) Where—

- C is in a long term foster placement and has been in that placement for at least one year, and

- C, being of sufficient age and understanding, agrees to be visited less frequently than required by paragraph (2)(c),

the responsible authority must ensure that R visits C at intervals of no more than 6 months.

[20] Department for Education (2014) Statutory guidance on children who run away or go missing from home or care, paragraph 31.

[21] Department for Education (2014) Statutory guidance on children who run away or go missing from home or care, paragraphs 32 and 69.

[22] Department for Education (2014) Statutory guidance on children who run away or go missing from home or care, paragraph 38.

[23] Section 104 Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012.

[24] Department for Education (2015) The Children Act 1989 guidance and regulations. Volume 2: care planning, placement and case review, para 8.33.

[25] Department for Education (2015) The Children Act 1989 guidance and regulations. Volume 2: care planning, placements and case review, paragraphs 2.11 and 2.12.

Fostering stocktake – response from the Minister

4 April 2018

Last month, a letter signed by 43 organisations and social work experts was sent to Nadhim Zahawi MP, Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Children and Families.

It outlined our detailed concerns about five of the 36 recommendations made by Sir Martin Narey and Martin Owers. We asked the Minister to reject these particular recommendations.

We have received a response from the Minister. It can be read below.

2018-0012952 – Response to Carolyne Willow – Director – Article 39 rec 4 April 2018.

Fostering stocktake – joint letter to the Minister

13 March 2018

The joint letter below has been sent to Nadhim Zahawi MP, Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Children and Families, to urge him to reject recommendations in the fostering stocktake to weaken children and young people’s legal protections.

The fostering stocktake was undertaken by Sir Martin Narey and Mark Owers.

Dear Minister

FOSTERING STOCKTAKE

We are organisations and individuals who worked together to defend the rights of children and families during the passage of the Children and Social Work Act 2017.

We write to respectfully ask that you reject those recommendations in the fostering stocktake which would require a change to the law (4, 6, 7, 8 and 33).

If acted on, recommendations 4, 6, 7, 8 and 33 would greatly weaken the legal protections enjoyed by our country’s most vulnerable children and young people. They each advocate a dilution of legal safeguards; together they communicate a lack of understanding for the origins and importance to children’s welfare of existing policy. We are doubtful that any of the legislative proposals would be compliant with the UK’s human rights obligations, both within the Human Rights Act and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Three of the recommendations (6, 7 and 8) were subject to detailed scrutiny and opposition during the passage of the 2017 Act. When the former Secretary of State for Education Justine Greening abandoned plans to permit local authorities to opt-out of their statutory duties in children’s social care, the Department issued a statement saying it had “listened to concerns”.

Our grave concerns were based on a sound understanding of the evolution of children’s law and safeguards and the UK’s human rights obligations. The policy goals communicated by the Department, during parliamentary debate and through written communications, including from the Chief Social Worker for Children and Families, pointed to a dangerous relaxation of legal protections for vulnerable children and young people.

We were very relieved when the Department cancelled its plans to ‘test’ deregulation of key legal safeguards and accepted our arguments about the intolerable risks to children’s welfare. That similar proposals have reappeared so quickly within a review that was supposedly about “the question of what different foster carers need – skills, expertise, support – in order to meet the diverse needs of today’s looked after children”[1] appears dishonourable. We hope you will reject recommendations 4, 6, 7, 8 and 33 for the reasons we set out below.

We remain absolutely committed to working with you and the Department in the interests of children, young people and families.

All good wishes

Article 39

Association of Independent Visitors and Consultants to Child Care Services

Association of Lawyers for Children

Association of Professors of Social Work

Become

British Association of Social Workers England

The Care Leavers’ Association

Children England

Children’s Rights Alliance for England

CoramBAAF

The Fostering Network

Howard League for Penal Reform

Independent Children’s Homes Association

Legal Action for Women

The MAC Project (Central England Law Centre and the Astraea Project)

Nagalro

National Association for People Abused in Childhood (NAPAC)

National Association for Youth Justice

National Association of Independent Reviewing Officers

Napo: the professional association and trade union for Probation and Family Court workers

NYAS

Parents of Traumatised Adopted Teens Organisation

Refugee Council

Siblings Together

Single Mothers’ Self-Defence

Social Pedagogy Professional Association

Southwark Law Centre

South West London Law Centres

UNISON

Dr Maggie Atkinson, freelance consultant and former Children’s Commissioner for England

Dr Liz Davies, Emeritus Reader in Child Protection, London Metropolitan University

Brid Featherstone, Professor of Social Work, University of Huddersfield

Anna Gupta, Professor of Social Work, Royal Holloway University of London

Pam Hibbert OBE

Ray Jones, Emeritus Professor of Social Work, Kingston University and St George’s, University of London

Dr Mark Kerr, Managing Partner, The Centre for Outcomes of Care

Jenny Molloy, Author, Adviser and Trainer

Kate Morris, Professor of Social Work, University of Sheffield

Peter Saunders, Founder NAPAC

Mike Stein, Emeritus Professor, University of York

June Thoburn CBE, Emeritus Professor of Social Work, University of East Anglia

Judith Timms OBE

Jane Tunstill, Emeritus Professor of Social Work, Royal Holloway, London University

Sue White, Professor of Social Work, University of Sheffield

Recommendation 4 asks the Department to remove authority from parents* whose children are being voluntarily accommodated under s20 Children Act 1989, so that there is automatic delegated authority to foster carers.

Existing statutory guidance (Children Act 1989 Volume 2, June 2015) describes the legal meaning and exercise of parental responsibility when a child is voluntarily accommodated. It accurately explains the child’s own legal right to make decisions. The guidance provides nuanced advice for those circumstances in which parents do not agree (for whatever reason) to delegate day-to-day parenting authority, reminding local authorities of their overarching legal responsibility to safeguard and promote the child’s welfare.

We cannot see how the 2015 guidance could be amended to categorically remove the right of parents whose children are accommodated under s20 (and children with capacity) to exercise and influence decision-making in day-to-day parenting matters. Such a move would require a radical change to the Children Act 1989 and to the Family Law Reform Act 1969 (in relation to 16 and 17-year-olds), neither of which we believe would be compatible with the UK’s human rights obligations.

*This would include adopters, special guardians and carers with child arrangements orders.

Recommendation 6 states that a single social worker should be given the task of supervising foster carers and discharging the local authority’s duties to children in long-term foster placements.

Since April 2015, care planning regulations have permitted a child in long-term foster care to be visited by his or her social worker only twice a year. There is no mention of this relatively recent regulatory change in the stocktake report, so it is impossible to know whether recommendation 6 was made in ignorance of the current legal position.

Besides quotes from two carers, the fostering stocktake report relies on the pilot conducted by Match Foster Care to advocate a change to care planning regulations. Yet the evaluation report from the Match Foster Care pilot describes a complex picture, including that two of the eight children in the very small sample were still visited by their own local authority social worker and there was ambivalence within local authorities about how they discharged their legal responsibilities. The researchers point to the 2015 regulatory change and associated guidance as “a valuable new framework”. Of most significance is the fact that the evaluation was not conclusive in respect of the benefits to children of a single, all-purpose social worker.[2]

Children having their own social worker is a fundamental safeguard and a lynch-pin of the care system. When it works well, it gives children the opportunity to develop a positive and trusting relationship through which they can safely explore their history and identity, share their experiences and raise any concerns. Regulations set down an expectation that the social worker will meet the child in private (though this is not rigid) which further underlines the importance of the child’s social worker being seen as there for them. The stocktake report itself states that children want to see more of their social workers.

Alongside this, foster carers require – and have the right to expect – their own specialist support.

The Supreme Court’s ruling last October, that local authorities can be held vicariously liable for the abuse of children in foster care, is pertinent to this particular recommendation, though there is no reference to it within the report. The Department will be aware that one of the potential outcomes of Armes (Appellant) v Nottinghamshire County Council is a greater degree of monitoring and supervision by local authorities, as indicated by Lord Reed: “It may be – although this again is empirically untested – that such exposure, and the risk of liability, might encourage more adequate vetting and supervision” [69].

Recommendation 7 urges the abolition of the independent reviewing officer (IRO) role. This recommendation could have a profound impact on the rights and welfare of children, including those who are remanded to custody, yet there is a dearth of evidence for it within the stocktake report.

The short section on IROs in the report contains an opinion expressed by a fostering manager and the views of two Directors of Children’s Services. A fourth quote describes the difficulties of ‘speaking truth to power’. The report is silent on who is intended to take on the statutory reviewing function and the monitoring of individual children’s human rights.

In addition to their vital statutory responsibility in relation to termination of placements for looked after children[3], children cannot be moved from accommodation regulated under the Care Standards Act 2000 to other arrangements without a statutory review of their care plan chaired by their IRO.[4]

Furthermore, the statutory guidance (Children Act 1989 Volume 3, January 2015) states, “No young person should be made to feel that they should leave care before they are ready. The role of the young person’s IRO will be crucial in making sure that the care plan considers the young person’s views. Before any move can take place, the statutory review meeting, chaired by their IRO, will evaluate the quality of the assessment of the young person’s readiness and preparation for any move”.

In other words, IROs have a critical statutory role and responsibilities in ensuring young people’s successful transitions to adulthood. These will be enhanced by the new provisions contained within the Children and Social Work Act 2017, including the extension of support to all care leavers to 25 years of age (from April 2018).

The fostering stocktake was not designed to review the role of IROs in safeguarding and promoting the rights and welfare of children in foster care, let alone across the care system. There was no call for evidence about the IRO role, and the authors of the stocktake report have no professional background or expertise in this policy area. The authors’ conclusion that “despite the commendable commitment of some individuals, we saw little to recommend the IRO role” displays a level of confidence out of synch with the report’s rudimentary analysis. This recommendation cannot be treated with any credibility.

Recommendation 8 asks for an assessment and consultation on the effectiveness, cost and value for money of fostering panels.

The ‘case’ for a review of fostering panels is made in a very short paragraph with a single quote from an unnamed “distinguished commentator”. There is no discussion of the evolution or legal basis of fostering panels.

The importance of fostering panels was debated by parliamentarians and the children’s sector during the passage of the Children and Social Work Act 2017. The government’s proposal that local authorities should be able to opt-out of having fostering and adoption panels was widely rejected – including, eventually, by Ministers.

The fostering stocktake was intended to be “a fundamental review”, it was undertaken over several months and received over 300 responses. Yet the stocktake report contains scant discussion of fostering panels. Unless the evidence to the stocktake was not properly collated, analysed and considered, we must conclude that contributors did not raise fostering panels as a significant area of concern. It is difficult therefore to see how this recommendation originates from this review.

Recommendation 33 recommends that local authorities should not presume that brothers and sisters in care should live together.

This is a radical proposal that flies in the face of established childcare practice and law. It implicitly dismisses decades of testimony from children in care and care leavers. It would require a change to the Children Act 1989, which we do not believe would be compatible with Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

The Children Act 1989 requirement to enable siblings to live together has an important legal caveat – it must be exercised so far as is reasonably practicable in all the circumstances of each individual child’s case. It sits within local authorities’ wider legal duty to safeguard and promote the welfare of children. The law allows flexibility so the individual child’s best interests prevails. The 2015 statutory guidance sums up:

Wherever it is in the best interests of each individual child, siblings should be placed together.

It is difficult to comprehend why the authors would wish to deny the importance of placing siblings together when this is in their best interests though, tellingly, they do not quote directly from the legislation.

We hope the Department will robustly defend current law and policy, recognising that being able to live alongside and have meaningful relationships with brothers and sisters continues to be a top priority for many children in care and care leavers.

The law on contact

We make one final observation in respect of the law. On page 82 of the stocktake report, the authors observe:

In 2013, the Government was persuaded that sometimes decisions on contact – however well intended – were not always in the best interests of the child. They decided that the long-established assumption that contact between a child or infant in care, and their birth family, was not in the child’s best interests, and should be removed from legislation. This followed significant concern about the distress caused to infants and younger children by contact, particularly contact which took place frequently, sometimes daily.

The authors state the presumption in favour of contact was removed by the Children and Families Act 2014. This is inaccurate.

The changes to s34 of the Children Act 1989 in respect of contact were twofold: firstly, to cross-refer to the pre-existing general duty to safeguard and promote the child’s welfare and, secondly, to remove any continuing duty to promote contact where a court has refused it, or the local authority has used its emergency powers to refuse contact. Neither of these provisions has the effect of removing the presumption of contact.

[1] Department for Education (2016) Putting children first. Delivering our vision for excellent children’s social care.

[2] Beek, M., Schofield, G. and Young, J. (October 2016) Supporting long-term foster care placements in the independent sector. Research report. Department for Education.

[3] Regulation 14, The Care Planning, Placement and Case Review (England) Regulations 2010.

[4] Section 22D Children Act 1989 (as amended by the Children and Young Persons Act 2008).

Bill granted Royal Assent – without the exemption clauses

27 April 2017

Royal Assent has been granted to the Children and Social Work Bill, which now becomes the Children and Social Work Act 2017. The eight clauses (Chapter 3 of the Bill) allowing local councils to opt-out of their legal duties towards children and young people are not part of the legislation. Our campaign to protect the rights of children and young people succeeded!

We successfully defended children’s rights!

2 March 2017

Children and Young People Now magazine reported earlier today that Ministers intend to support amendments tabled by Shadow Children’s Minister Emma Lewell-Buck, to remove the exemption clauses.

By the evening, the Education Secretary Justine Greening had added her name to the amendments, which means the clauses will be deleted once and for all on Tuesday, 7 March.

The Together for Children campaign has the backing of 53 organisations and 160+ individual experts. Over 108,000 members of the public signed our online petition.

Some reactions from our campaign members to today’s fantastic news:

Jenny Molloy, author of Hackney Child, said:

“The success of the Together for Children campaign to urge the removal of the exemptions for protecting looked after children shows that the voice of experts by experience and professionals is loud and clear. Children can now be safe in the knowledge that their rights and entitlements to protection and safety are still in place.”

Jacki Rothwell, Chair of the National Association of Independent Reviewing Officers, said:

“This is a triumph for common sense. NAIRO is tremendously grateful to everyone who contributed to the Together for Children campaign.

“We have made relationships with other campaigners that will stretch long into the future

“Most of all, NAIRO is relieved that children and young people can continue to rely on the rights and duties that have been built up over the years to help them stay safe and get a fair deal in life.”

John Simmonds, OBE, Director of Policy, Research and Development at CoramBAAF, said:

“We are delighted that the government had seen the serious error in pursuing the clauses ‘Testing New Ways of Working’ in the Children and Social Work Bill. There is no doubt that innovation and development is much needed in the care sector. But this must not happen by potentially undermining the rights of children who need the protection of the law wherever they live. Independent Reviewing Officers and Adoption and Fostering Panels were offered up as potential sacrifices in pursuing innovation without ever acknowledging the child centred focus at the centre of both.

“It is to be hoped that in the debate on the rest of the Bill, children are at the Centre of what is put into new law and lessons have been learnt about how not to do this. That would be the most beneficial development from this unfortunate experience.”

Peter Saunders, Founder of the National Association for People Abused in Childhood, said:

“This victory for common sense, well this victory for children, has been hard fought and whilst it should never have been a fight (how can we ever seriously consider knowingly jeopardize our children’s safety?) it is a fight that is won. Thank goodness. And it has been won mostly because of the tenacity, the energy and love shown by Carolyne Willow. I have known Carolyne for many years (often wondered where she gets that energy!) and I know for certain that what drives her is the desire to do what is right for our most precious asset, our children.”

BASW (British Association of Social Workers) Chief Executive Dr Ruth Allen said:

“BASW strongly opposed the exemption clauses from day one. Our online survey and a postcard campaign found members were strongly against these clauses and almost 1000 BASW members lobbied their MPs through the postcards.

“It was clear from the start that these divisive and potentially dangerous clauses were not needed for innovation in children’s services. The next step for this government has to be about engaging with the profession to secure real improvements that would enhance rather than dilute children’s rights and promote good social work practice in all services

“BASW thanks its members for all their fantastic support to ensure that children’s rights were upheld and the profession listened to.”

Professor Ray Jones, Kingston University and St George’s, University of London, said:

“It is a relief and positive that the government is showing itself to be reflective and willing to listen and reconsider. This is potentially a hopeful and helpful sign for the future of active engagement and consultation rather than the ‘doing to’ style of recent times. It also shows the potential strength of coherent and energetic collective professional, political and public opposition to proposals which had inherent in-built risks and dangers.”

Professor Nigel Thomas, University of Central Lancashire, said:

“This shows what can be achieved by a dedicated, focused and united campaign. I sincerely hope that children’s entitlement to consistent quality of services is now secure, for the time being at least.”

Matthew Egan from UNISON said:

“This is really welcome news. Social workers have overwhelmingly opposed these reckless proposals from the outset. A survey of 2,900 UNISON social worker members back in the autumn showed that not only were they unwanted by the vast majority of the profession but they would also lead to more children being placed at risk.”

Sara Ogilvie, Policy Officer for Liberty, said:

“When the vast majority of social workers, child welfare experts, survivors of abuse, children’s rights campaigners and peers are uniting to tell you your plans will put vulnerable young people and families at risk, serious alarm bells should be ringing.

“We’re delighted the Government seems to have seen sense and u-turned, but it remains astonishing that these proposals – which would have razed 80 years of child protection laws to the ground and were introduced with no consultation or evidence base – ever saw the light of day. We hope ministers will now do their job and stand up for children’s rights instead.”

Legal Action for Women and Single Mothers Self Defence said:

“We are delighted to have helped force the government to back down on allowing local authorities to opt out of statutory child protection responsibilities. These measures had nothing to do with ‘innovation’ as the government claimed. When more children are in care than any time in the past 30 years, this would have been a huge incentive for greater privatisation of children’s services, leaving the most vulnerable and traumatised children even more unprotected from market forces. Determined opposition made the difference. Let’s have more of it so we can stop so many children being taken into care.”

Chloë Cockett, Policy and Research Manager at Become, said:

“Become welcomes this decision by Government to support the amendments to the Children and Social Work Bill that will see the removal of the exemption clauses. This turnaround demonstrates that they’re listening to the large number of organisations and people who are actively trying to work with them to secure the best possible futures for children in care and care leavers.

“We want to see all children in care and care leavers receive the very best care from their corporate parent. As such the focus of the Children and Social Work Bill, and the work of the Government going forward, should look at enhancing the rights of children in care and care leavers and ensuring that the support they receive is consistently funded and implemented across the country.”

Legal organisations – letter in The Times

22 February 2017

A letter from leading legal organisations, against the exemption clauses, was published in The Times newspaper today:

Sir,

Under proposals in the Children and Social Work Bill, this and future governments will be able to exempt individual local authorities from existing statutory duties to children and young people without further parliamentary approval. Put simply, the legal rights of children will depend on where they live.

After the defeat of the clauses in the House of Lords, some core duties to children in need are protected from exemption applications, but there is no protection for the most vulnerable group of all: the 50,000 children who have been found by the court to have suffered significant harm and have been placed in care under a care order.

This process involves a judge entrusting a local authority with legal parental responsibility, overriding the legal responsibility of the child’s parents. Unlike real parents, the new corporate parents may in future have different legal duties to their children from the corporate parents next door. We must not allow these clauses to pass into law.

MARTHA COVER AND DEBBIE SINGLETON, Co-Chairwomen, Association of Lawyers for Children

ROBERT BOURNS, President, The Law Society

PHILIP MARSHALL QC, Chairman, Family Law Bar Association

NIGEL SHEPHERD, Chairman, Resolution

Professor Eileen Munro says exemption clauses are “a serious danger”

10 February 2017

The London School of Economics professor whose work has been consistently cited by Ministers as the inspiration for controversial clauses in the Children and Social Work Bill has deserted the policy.

In an email yesterday (9 February) to Article 39’s Director, Shadow Children’s Minister Emma Lewell-Buck and former Children’s Minister Tim Loughton, Professor Eileen Munro said:

“I have been reading the debates in Hansard and the submissions … I’ve also been meeting with some of those who oppose the Bill and I have reached the conclusion that the power to have exemption from primary and secondary legislation creates more dangers than the benefits it might produce … While I understand and respect the motivation of the current Government, there is a serious danger in having such wide-reaching powers in statute. Some future Secretary of State might use them in ways that are completely contrary to the current intentions and consequently subvert the will of Parliament.”

Read more:

Community Care

Children and Young People Now

BBC News

MPs ignore severe child protection warnings from large body of experts

9 February 2017

A new report shows a large body of experts warned MPs of the grave danger of undoing decades of legal protection for vulnerable children and young people.

This advice was ignored by the Committee of MPs debating the Children and Social Work Bill, which contains radical opt-out clauses allowing individual councils to be excused from child protection and welfare duties.

The Committee invited expert submissions before it voted on the clauses last month.

Today, the campaign group Together for Children releases a synopsis of the expert advice. This brings together all of the evidence for the first time, and shows:

- 46 individual experts and organisations warned the Committee that allowing councils to opt-out of duties could cause great harm and reverse decades of progress in protecting very vulnerable children and young people

- Individual experts who provided evidence to the Committee have more than 650 years’ collective experience of working with vulnerable children and young people

- The Committee was given numerous case studies of individual children and young people whose welfare and safety depends on council duties

- Only one of the 47 submissions on the opt-out clauses supported the Government’s plan to break up children’s law

- This was the first public consultation on the Bill. There were no Green or White Papers, and no consultation has taken place with those who will be directly affected – including children living in foster care, children’s homes, disabled children, young carers and young people who have left care.

The radical opt-out plans were rejected by the House of Lords in November. The following month, Children’s Minister Edward Timpson MP tabled amendments to reinstate the controversial clauses, and these were pushed through on 10 January, on a 10-5 vote split along party political lines.

None of the 10 Conservative MPs who voted to reinstate legal opt-outs referred to any of the expert warnings submitted to the Committee.

Martha Spurrier, Director of Liberty, said:

“It is scandalous that the Government continues to ignore vital evidence at every juncture – wilfully placing cost-cutting ahead of the rights and safety of our children.

“Its blind commitment to effectively dismantle almost a century of crucial child protection laws, against the wishes of professionals on the frontline, experts, Peers and the public, serves shames on our great democracy.

“These proposals are fundamentally dangerous and will expose vulnerable young people to the risk of abuse and neglect – principled MPs have no option but to shut them down.”

Judith Timms OBE speaking on behalf of Nagalro, the professional association of children’s guardians appointed by the courts to advise on children’s welfare, said:

“Children’s rights shouldn’t depend on their postcode. It is both unworkable and unethical. If these exemption clauses continue to be pushed through, our country’s most vulnerable children and young people will no longer have any certainty that the law will protect them. It is unacceptable that our members should be required to represent the interests of children in different ways depending on where they live, or have to keep children and the courts updated on which local authorities have opted- out of which legal duties and obligations.”

Emeritus Professor of Social Work, June Thoburn CBE, said:

“None of the substantial body of research on the workings of the Children Act 1989 points to the need for any specific sections of the legislation to be suspended on the grounds that they are impeding flexible and good quality practice. These clauses are a severe threat to children’s rights and it’s bitterly disappointing the Government appears so fixed on ignoring the social work profession.”

Jacki Rothwell, Chair of Trustees of the National Association of Independent Reviewing Officers, said:

“It is disquieting that, despite so many opportunities over the past few months, the proponents of the exemption clauses have not provided any evidence that current legislation is a barrier to innovation, different ways of working or improving outcomes for vulnerable children. Taken together with the apparent lack of interest shown by the Public Bill Committee in the first public consultation on the Bill’s provisions, we have to ask what is the real driver for these exemption clauses. Who stands to benefit from these clauses because it certainly isn’t vulnerable children?”

Professor Mike Stein has been researching and supporting improvements in leaving care since the 1970s. He said:

“From the Children Act 1948 onward the legal and policy framework for young people leaving care has been strengthened by new duties derived from independent research, consultations with care leavers, policy makers and practitioners; inspections; and, leadership from government departments. This has resulted in a comprehensive and universal legal framework. It is crucial that young people leaving care, wherever they happen to live, continue to be legally entitled to the full range of statutory support. There are great risks in fragmenting an established and comprehensive universal service, not least a return to the failures of a discretionary system which resulted in both territorial and service injustices.”

John Simmonds OBE, Director of Policy, Research and Development at CoramBAAF, said:

“As individual citizens, all children have a right to be protected by the law wherever they live and whatever their circumstances. This could not be more important than for those children at risk and in need where the State becomes directly involved in safeguarding them or planning for their immediate and long-term welfare. The clauses in the Children and Social Work Bill, misleadingly termed ‘power to test different ways of working’ fundamentally challenge those rights and seeks to remove them. The House of Lords recognised this in deleting these clauses.

“If the law needs to be changed to protect and safeguard children, then this must be subject to full Parliamentary scrutiny as it is and required for every other citizen. It is not a matter to be tested by a small group of individuals in a closed discussion in a government department.

“Children deserve and need their fundamental rights to be protected and enhanced. And the Commons has a unique opportunity to ensure that this continues now and into the future.”

Carolyne Willow, Article 39 Director, said:

“Lively and heated debates are happening within Parliament, and all over the country, about the future of our democracy and the rule of law. Yet here we have a Bill slipped into Parliament, without any public consultation, which threatens to destroy the legal scaffolding holding up the vital help and protection we offer to our most vulnerable children and young people. It is the single biggest threat to our child welfare system I have seen. MPs in that Committee had the great privilege and responsibility of making law for abused, disadvantaged and vulnerable children. They chose not to listen and learn from the huge body of expertise, and now we have a Bill that once again is unworthy of children.”

Notes

1 The report is released by Together for Children, the campaign group formed to fight the opt-out clauses. 49 organisations and more than 150 individual experts are members of the campaign group. Its online 38 Degrees petition has been signed by more than 107,000 members of the public.

2 The Public Bill Committee scrutinising the Children and Social Work Bill issued its invitation for expert evidence on 6 December. Submissions on the exemption clauses had to be made by 6 January 2017, to have any chance of influencing MPs.

3 The Shadow Children’s Minister, Emma Lewell-Buck MP, has tabled amendments to once again remove the clauses from the Bill. A date for the Bill’s next Commons stage has not yet been fixed. MPs begin recess tomorrow and will return on 20 February.

Exemption clauses raised at Education Questions

6 February 2017

Education Questions in the House of Commons this afternoon (6 February) included a question about local authority legal opt-outs. You can watch the exchange between Shadow Minister for Children and Families, Emma Lewell-Buck MP, and the Minister for Vulnerable Children and Families, Edward Timpson MP, by clicking on the link below.

Education Questions – exemption clauses (clip from Parliament TV)

Evidence to Commons Committee published

13 January 2017

The House of Commons Public Bill Committee scrutinising the Children and Social Work Bill has now published all of the evidence it received about the exemption clauses, before it voted to reinstate them on Tuesday (10 January). This reveals that just one of 48 submissions* supported the exemption clauses.

*Two submissions were made by the same individual, which means the Committee received submissions from 47 separate organisations and individuals. Of these, 44 opposed the exemption clauses and a further two expressed concerns.

EVIDENCE TO PUBLIC BILL COMMITTEE – EXEMPTION CLAUSES

The submissions listed above are taken from the Public Bill Committee / Parliament website, which you can access here. (Submissions are published after the Committee meets).

Exemption clauses back in the Bill

10 January 2017

As we anticipated, the Public Bill Committee has voted 10-5 to put the exemption clauses back in the Children and Social Work Bill. Evidence received by the Committee on the exemption powers was unanimous in opposing Children Minister Edward Timpson’s amendments.

Of 34 submissions published to date, relating to the exemption clauses, 0 supported the Government’s position and 34 opposed.

The Bill had been cleared of the exemption clauses in November, after the Government was defeated in the House of Lords.

These clauses, if they remain in the Bill, will allow individual councils to be excused from their children’s social care legal duties required by Acts of Parliament (and accompanying subordinate legislation) from 1933 onwards. The Government has decided that six sections of the Children Acts 1989 and 2004 will, however, be exempted from the exemptions.

The House of Commons Committee considering the Bill is weighted in the Government’s favour so today’s vote was expected.

Together for Children will continue to defend universal children’s social care rights, and press for Green and White Paper consultation.

Read the evidence here (scroll down to ‘written evidence’).

MPs urged to reject exemption clauses – first evidence to Public Bill Committee

3 January 2017

Five of 13 submissions published by the Public Bill Committee scrutinising the Children and Social Work Bill oppose government amendments that seek to reinstate the exemption clauses. None of the 13 documents express any support for the revised exemption clauses tabled by Children’s Minister Edward Timpson in December, following the House of Lords defeat the previous month.

All of the 13 submissions were made shortly after the Committee’s call for evidence on 6 December. Other evidence will not be published until after the Committee has voted on the exemption clauses, though it will be considered by MPs if submitted before 9 January.

The submission from Women’s Aid states:

“We call on Members of Parliament to protect universal children’s social care statutory duties as the Bill proceeds through the House of Commons.”

Women Against Rape says:

“We are completely opposed to government amendments which seek to remove statutory protection in the name of ‘innovation’, effectively privatising children’s services.” [emphasis in original]

The Independent Children’s Homes Association warns:

“this Bill seeks to sweep away universal entitlement and replace it with vicarious contingency locally determined, severely affecting the most important factor in the upbringing of vulnerable children, the secure emotional base.”

The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health submission states:

“The RCPCH calls on MPs to reject New Clauses NC2-NC9 from the Bill and protect the legislative framework for children’s social care.”

Legal Action for Women explains:

“We are opposed to New Clauses 2 and 3 (NC2, NC3) proposed by Edward Timpson, which re-introduce the Clauses removed by the House of Lords and allow local authorities to “opt out” of statutory child protection measures so that they could be outsourced and eventually “run for profit”.

Submissions can be read here.

Date set for Commons vote on exemption clauses

16 December 2016

The Committee of MPs scrutinising the Children and Social Work Bill will consider Government amendments to reinstate the exemption clauses on Tuesday 10 January 2017. The session will begin at 09.25am.

We are urging everyone with personal and/or professional experience of children’s social care to submit evidence no later than Friday 6 January.

Information about how to submit evidence is available on the Parliament site here.

You can find out about the revised clauses on this part of the Together for Children site.

Committee membership

Chairs:

- Mrs Anne Main (Conservative MP, St Albans)

- Phil Wilson (Labour MP, Sedgefield)

Other members:

- Maria Caulfield (Conservative MP, Lewes)

- Stella Creasy (Labour MP, Walthamstow)

- Thangam Debbonaire (Labour MP, Bristol West)

- Marion Fellows (SNP MP, Motherwell and Wishaw)

- Suella Fernandes (Conservative MP, Fareham)

- Kate Green (Labour MP, Stretford and Urmston)

- Simon Hoare (Conservative MP, North Dorset)

- Seema Kennedy (Conservative MP, South Ribble)

- Mrs Emma Lewell-Buck (Labour MP, South Shields)

- Steve McCabe (Labour MP, Birmingham, Selly Oak)

- Huw Merriman (Conservative MP, Bexhill and Battle)

- Amanda Milling (Conservative MP, Cannock Chase)

- Tulip Siddiq (Labour MP, Hampstead and Kilburn)

- Mr Robert Syms (Conservative MP, Poole)

- Edward Timpson (Conservative MP and Children’s Minister, Crewe and Nantwich)

- Michael Tomlinson (Conservative MP, Mid Dorset and North Poole)

- Helen Whately (Conservative MP, Faversham and Mid Kent)

Government says it will reinstate exemption clauses

5 December 2016

Children’s Minister Edward Timpson MP confirmed today that the Government plans to reinstate the exemption clauses, now that the Children and Social Work Bill has reached the Commons. Writing in Community Care, Timpson said he planned to reinstate “a much altered and improved set of clauses”.

No further detail was provided at this afternoon’s Second Reading debate on the Bill, though Nick Gibb MP, Minister for School Standards, told MPs the Government had “reviewed and substantially revised the clauses”.

The news was met with strong opposition in the Commons. Conservative MP Tim Loughton, who was Children’s Minister between 2010 and 2012, praised “the good work of the House of Lords” in removing the exemption clauses and said:

“a child needs protection wherever he or she may be in the country. We cannot have a competition between different areas on ways of looking after vulnerable children, some of which will not work and some of which might. Every child needs the protection of the law as set out by Parliament, and it should not be subject to a postcode lottery, as is convenient for certain local authorities.”

Labour Shadow Children’s Minister, Emma Lewell-Buck MP, also commended the work of Peers and highlighted the recent LaingBuisson report published by the Department for Education:

“I wish to congratulate peers on defeating the Government and forcing them to remove dangerous clauses from the Bill that would pave the way for privatisation of children’s social care. It is scandalous that these clauses are soon to reappear at Committee stage.

“The Government have denied time and again that the opt-out clauses were about privatisation, yet late last week, two years after it was written and after an inexplicable delay in responding to freedom of information requests, the Department for Education released a report, … which sets out how children’s social care can be moved out of local authority control – a report which states that independent contractors have said that they are willing to play the long game and wait for councils to hand over the majority, if not all, of their children’s social care services after they have developed their experience in children and families social work.”

Peers succeed in their defence of children’s rights

8 November 2016

Clause 29 has been defeated in the Lords by 32 votes. Lord Ramsbotham’s amendment to leave out the controversial clause was supported by 245 Peers, and 213 Peers backed the Government.

Together for Children members’ reactions to the brilliant news are set out below.

Carolyne Willow, Director of Article 39 children’s rights charity, said:

“Today’s vote is an incredibly strong affirmation of children’s rights and the unique role Parliament has in creating, revising and strengthening children’s law.

“The fundamental flaw with Clause 29 was that it allowed highly vulnerable children to have different legal protections on the arbitrary basis of where they happen to live. Peers have determined this to be unacceptable.

“We hope the Government will now listen and respond to the huge opposition its plans have provoked. The very worst response to this defeat would be for Ministers to simply reinsert the Clause when the Bill enters the Commons.”

John Simmonds, Director of Policy, Research and Development at CoramBAAF, said:

“The Lords have made it clear that the fundamental rights of children and families to the equal application of the law wherever they live is not to be tampered with. Where the law is thought not to be working in the best interests of children, then Parliament and Parliament alone can only introduce new law or amend existing law. It has taken generations to firmly establish this core principle and one vote to remind us just how vital it actually is.”

Martha Spurrier, Director of Liberty, said:

“Our child protection laws are the result of a century of learning, public debate and parliamentary scrutiny – but, with no research or proper consultation, this Government has decided they are dispensable.

“Well done to the Lords for doing the Government’s job, listening to the concerns of social workers and campaigners, and standing up for children’s rights. If the Prime Minister really wants a country that works for everyone, she must now prove it by scrapping this dangerous and undemocratic plan once and for all.”

UNISON general secretary Dave Prentis said:

“Ill-conceived government plans to remove statutory duties protecting children should never have been put forward.

“Social workers recognised the danger of removing decades of child protection law, it’s a pity ministers didn’t bother to ask them about the risks posed by the proposals.

“The Lords have seen sense and voted against removing essential protection for children.”

A spokesperson for youth homelessness charity Depaul UK said:

“We are delighted the Government was defeated today in the Lords. The essential safeguarding provided by the Children Act must be fully protected for the sake of the most vulnerable in society. Maintaining every local authority’s duties to children who are at risk is the very foundation of our safeguarding system.”

Martha Cover, children law barrister and Co-Chair of the Association of Lawyers for Children, said:

“The House of Lords has pulled us back from the brink of a dangerous Bill today.

“Local authorities already have wide powers to put their houses in order. They can and do innovate and reduce red tape and bureaucracy within their own departments. Although this is the ostensible reason given for the need to undermine the legal child protection framework, none of the examples given so far as to how the exemptions might be used are about red tape and bureaucracy. They are in fact about reducing the time that social workers spend talking to children and getting to know them. This is what social workers do, and what they want to do more of. The answer is simple: reduce their case loads. They are also about undermining the position of independent reviewing officers still further. It will come as no surprise to child care lawyers that the great majority of front line social workers and IROs do not support the exemption clauses. They know that if these clauses are enacted, they will open the legal gateway for local authorities to reduce or dispense with their duties to children in need.”

Ray Jones, Emeritus Professor of Social Work at Kingston University and St George’s, University of London and a former director of social services, said:

“Surely now the new Secretary of State will be advised and recognise that she has inherited poorly drafted legislation which threatens the rights of children and potentially puts to one side the responsibilities of statutory services to help families and children. It is time for reflection and a re-think. It would be sensible to withdraw this widely-criticised and opposed Bill. The new Secretary of State deserves the opportunity to consult and re-construct rather than battling on with what would be discredited, incoherent legislation covered in the sticking plasters of enforced patchy amendments.”

Jacki Rothwell, Chair of the National Association of Independent Reviewing Officers, said:

“Many very vulnerable children will not know what the House of Lords has done today to safeguard them from further harm but it will impact on their futures. Now is the time for the government to work with those on the frontline, including NAIRO members, to innovate in ways which improve the lives of vulnerable children without denying them hard won rights to protection from harm.”

Brigid Featherstone, Co-President of Association of Professors of Social Work, said:

“The contributions in the House of Lords today highlight the importance of the Government engaging in meaningful consultation across the sector to capture the evidence and wisdom that is out here in relation to promoting good practice. Ethics, evidence and human rights must be at the heart of practice in such a consequential area as promoting and safeguarding the welfare of children. The proposals in the Bill were lacking in all three respects but we now have an important opportunity to work together to get things right.”

Ross Little, Chair, National Association for Youth Justice, said:

“We are very pleased with the decision by the House of Lords to challenge the Government on their plans to allow councils to opt out of their legal responsibilities to the most vulnerable children in our society. The plans put forward by the Government were ill-thought-out, poorly explained and potentially very damaging. We congratulate the work of Article 39 and Lord Ramsbotham in winning the vote in the Lords to delete Clause 29. We hope that the clause does not re-appear at a later stage in the process.”

Anne Neale from Legal Action for Women said: